EU carbon values under pressure on recession, demand worries

Sentiment in the European carbon price market remained bearish in the week to Feb. 2 amid muted demand. Traders and analysts have said they expect prices to remain around Eur60-65/mtCO2e in the coming week, with macroeconomic concerns and reduced power generation dominating headlines.

EU Allowances under the bloc’s Emissions Trading System were trading at Eur63.22/mtCO2e at 1038 GMT on Feb. 2 compared with Eur63.58/mtCO2e on Jan. 26.

Platts, part of S&P Global Commodity Insights, assessed EUA contracts for December delivery at Eur62.19/mtCO2e on Feb. 1.

Many analysts have downwardly revised their EUA price forecast for 2024 due to recession concerns and reduced emissions from the power and industrial sectors.

Analysts at S&P Global expect 2024 average prices to plunge to Eur63.90/mtCO2e compared with Eur85.30/mtCO2e in 2023 and Eur81.50/mtCO2e in 2022.

“EUA prices are expected to decline further due to the expectation of a technical recession despite a resilient labor market,” they said in a recent note. “The slowdown is broad-based affecting sectors like construction, manufacturing, and services. We expect prices to hit the high Eur50/mt mark threshold in February.”

Climate reforms

On Feb. 6, the European Commission is likely to recommend that the EU commit to a 90% reduction in emissions by 2040, which could provide some relief to declining prices.

This target is being backed by several EU countries, but climate policies have become heavily politicized recently, with farmers across Europe currently protesting against costly clean energy regulations.

But many policymakers, analysts and climate scientists insist that the EU must commit to this if it has any realistic chance of reaching net zero by 2050.

The European Council has set a goal for the EU to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared with 1990, and become climate neutral by 2050.

Meanwhile, the inclusion of the maritime sector in the EU ETS, opens up a new set of buyers for EUAs.

The European Commission published a document Jan. 31 attributing each shipping company to an EU member state to help these companies register for EU ETS compliance.

Shipping companies can now open holding accounts to trade EUAs and manage their ETS exposure.

Under the EU ETS guidelines, shipping companies must surrender their first ETS allowances by Sept. 30, 2025, for emissions reported in 2024.

The EU has also agreed on a phase-in period to give the industry some preparation time, with the ETS covering 40% of the emissions in 2024, 70% in 2025 and 100% from 2026 onward.

The shipping sector’s inclusion is projected to add emissions of 90 million mtCO2e this year, which is around two-thirds of the sector’s emissions.

CBAM extension

Meanwhile, the European Commission extended has the period for declarants to submit their quarterly reports under the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism by 30 days from the original deadline, after a significant number of importers experienced technical issues that led to some businesses being unable to make submissions.

The new carbon border tax entered into application in a transitional phase Oct. 1, with the first reporting period for importers originally set to end Jan. 31.

CBAM essentially levies a tax on imports of selected carbon intensive materials and products (including aluminum, cement, electricity, fertilizers, hydrogen, iron and steel) into the EU, removing the gap between the EU ETS carbon price and the export country of origin’s carbon price.

The main purpose of the tax is to reduce the risk of carbon leakage — as a result of EU industries locating abroad — and encourage importer nations to introduce their own carbon markets and, so, limit CBAM impacts on their traded goods.

No penalties will be imposed on reporting declarants experiencing difficulties in submitting their first CBAM report, the commission said.

“While the system has been working well in previous days with data and many reports being submitted successfully, technical teams are working around the clock to rectify remaining issues,” the EC said.

The commission has encouraged those reporting declarants that do not encounter any major technical issues to submit their CBAM report by the end of the reporting period.

Author: Eklavya Gupte, eklavya.gupte@spglobal.com

EU steel emissions to see higher penalties as free allowances get taken away

EU steel production emissions will be gradually penalized further from 2026 through to 2034, which will lead to higher costs for existing steel production and incentivize lower-emissions output.

The penalties based on carbon emissions emitted by key steel and raw materials production processes will increase under the EU’s Emissions Trading System and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

EU steel processes will see the quantity of allocated free emissions allowances reduce in a non-linear trajectory from existing levels to zero by 2034. This will lead to heavier emissions costs for producers forced to buy EU Allowance, or EUA, carbon permits for compliance. The ETS free allowances are to be replaced by the CBAM from 2026 and 2034.

The removal of free EUAs would lead to additional costs for steel producers exceeding benchmark levels. Based on reference values for blast furnace-based steel mills producing met coke and iron ore sinter, higher costs of around Eur144.72/mt of finished steel can be expected, with a reference cost for electric arc furnace carbon steel producers of Eur18.93/mt of steel, using July average EU carbon prices and analysis by S&P Global Commodity Insights.

Related podcast: How is Europe’s steel industry rising to the challenge of energy transition

Steel producers with higher operating emissions will be encouraged to adapt steel processes and raw materials usage, as well as invest, to transition more of the region’s production to steel with lower embedded emissions.

The alternative would be to pay to offset the difference, assuming risks on forward carbon pricing and using any banked EUAs available.

The dilemma may be how to manage the higher costs of alternative raw materials such as iron ore pellets and high-grade ferrous scrap, along with supporting the energy transition to use green hydrogen and renewable power and cut coal-based fuels.

Investment in new plants and processes to achieve low-emissions steelmaking have pushed steel companies such as Salzgitter and Thyssenkrupp to seek government subsidies and grants.

A move to certify emissions in steel production and mining, logistics and processing has allowed carbon-accounted steel markets to develop in the past few years.

Europe has led the interest in carbon-accounted steel and industry decarbonization, followed by Canada and the US and some markets in Asia.

The CBAM’s effect on global seaborne steel trade is anticipated to further deepen the interest in carbon-accounted steel production and marketing.

Steel end-users and steel processing and distribution groups are looking to adapt steel supplies for consumers, and to meet new procurement targets and standards. This is also pushing for more transparency around steel’s carbon intensities, with interest led by industry and government bodies.

Steel producers are currently obliged by the EU to report and pay for emissions from installations in the region based on the defined categories of hot metal production, iron ore sintering, met coke production and two types of electric arc furnace steel production.

Scope 3 emissions for steelmakers, emitted from raw materials mining, processing and logistics, are not included under the ETS reporting scheme.

The incoming CBAM will be applied for steel, pig iron and direct-reduced iron product imports, among other markets such as for aluminum, cement, hydrogen and fertilizers.

The CBAM aims to require the same carbon emissions cost being paid for imports as relevant to EU steel and other products, ensuring a level playing field and complying with World Trade Organization rules. The mechanism will take into account EU ETS and free allowances levels for applicable markets as the frameworks converge, in relation to certified carbon emissions for import products.

CBAM will develop reference emissions values for product categories where reported carbon intensity data is not available prior to the mechanism’s launch on Jan. 1, 2026.

Importers to the EU will buy CBAM certificates to comply with any outstanding product emissions costs required. CBAM certificates will price based on weekly EU Allowance pricing.

The CBAM will enter into application in its transitional phase on Oct. 1, with the first reporting period for importers ending Jan. 31, 2024.

Reporting obligations and information sought from EU importers of CBAM goods, as well as a provisional methodology for calculating embedded emissions released during the production process of CBAM-related imports will be specified further in an Implementing Regulation. This legislation will be adopted by the European Commission after consulting the CBAM Committee.

The CBAM and ETS will apply charges with adjustments available for steel production processes through to 2034, which mean steel imports are expected initially to pay a similar carbon-based charge. CBAM is not expected to include upstream Scope 3 emissions, emitted from mining and processing, logistics and transportation of steel raw materials.

Imported flat and long steels produced with ferrous scrap and direct-reduced iron may compete with more emissions-intensive steel in certain grades and segments.

European steel markets and user groups are increasingly differentiating on pricing and demand between steel with carbon emissions data reported for Scope 1, 2 and 3, and whether direct emissions cuts or mass balance-based calculated emissions reductions are involved.

A variation between the ETS and steel production emissions compliance, and a new focus on product-level carbon intensity with upstream emissions is seen. This considers emissions in the entire production chain and any differences between steel imports and EU origin products.

EU safeguards already place quotas on steel imports by origin. CBAM is designed to help ensure imports are on a level playing field with EU products and emissions costs, and support investments in industry decarbonization.

The reduction in the steel sector’s free EUAs may lead to higher compliance costs for steel producers if they cannot decarbonize at the same rate, as companies fund high capital greenfield plants.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM): Questions and Answers

Why is the EU putting in place a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism?

The EU is at the forefront of international efforts to fight climate change. The European Green Deal set out a clear path towards achieving the EU’s ambitious target of a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990 levels by 2030, and to become climate-neutral by 2050. In July 2021, the Commission made its Fit for 55 policy proposals to turn this ambition into reality, further establishing the EU as a global climate leader. Since then, those policies have taken shape through negotiations with co-legislators, the European Parliament and the Council, and many have now been signed into EU law. This includes the EU’s plan for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

As the EU raises its climate ambition and less stringent environmental and climate policies prevail in some non-EU countries, there is a strong risk of so-called ‘carbon leakage’ – i.e. companies based in the EU could move carbon-intensive production abroad to take advantage of lax standards, or EU products could be replaced by more carbon-intensive imports. Such carbon leakage can shift emissions outside of Europe and therefore seriously undermine EU as well as global climate efforts. The CBAM will assess the emission released in producing goods and equalise the price of carbon between domestic products and imports of a selected number of products. Hence it will ensure that the EU’s climate objectives are not undermined by production relocating to countries with less ambitious policies. The CBAM is therefore a climate measure to prevent the risk of carbon leakage and support the EU’s increased ambition on climate mitigation, while ensuring WTO compatibility. Over a period of eight years, CBAM will also gradually replace the free allowances given under the EU Emission Trading System (ETS). In this way, CBAM will be an important incentive for EU producers to reduce emissions.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, as co-legislators, signed the final CBAM Regulation on 10 May 2023. The provisions underpinning the CBAM, and its operational features will now progressively enter into force and application.

How will the CBAM work?

In accordance with EU’s international policies and commitments, CBAM has been designed to comply with EU’s international obligations including World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

The CBAM system will mirror the EU ETS and will work as follows:

• CBAM will be applied on the actual declared carbon content embedded in the goods imported in the EU, according to a formula that will reflect the effects of the EU ETS on the production of similar goods in the EU.

• As from the entry into force of the final regime of CBAM in 2026, EU importers will buy CBAM certificates corresponding to the carbon price that would have been paid, had the goods been produced under the EU’s carbon pricing rules.

• Conversely, if a non-EU producer has already paid a carbon price in a third country on the embedded emissions for the production of the imported goods, the corresponding cost can be fully deducted from the CBAM obligation.

• The CBAM will therefore help reduce the risk of carbon leakage while encouraging producers in non-EU countries to green their production processes and countries to introduce carbon pricing measures.

To provide businesses and other countries with legal certainty and stability, the CBAM will be phased in gradually and will initially apply only to a selected number of goods at high risk of carbon leakage: iron/steel, cement, fertilisers, aluminium, hydrogen and electricity generation. In a transitional period, a reporting system will apply as from 1 October 2023 for those goods with the objective of facilitating a smooth roll out and to facilitate dialogue with third countries. Importers will start paying the CBAM financial adjustment in 2026.

How does CBAM interact with the Emissions Trading System (ETS)?

The EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) is the world’s first international emissions trading scheme and the EU’s flagship policy to combat climate change. It sets a cap on the amount of greenhouse gas emissions that can be released from power production and large industrial installations. Allowances must be bought on the ETS trading market, though a certain number of free allowances is distributed to industry to prevent carbon leakage. In order to step up the incentive to decarbonise, the CBAM will progressively become an alternative to this. Under the EU’s ETS, the number of free allowances for all sectors declines over time so that the ETS can have maximum impact in fulfilling the EU’s ambitious climate goals. For the CBAM covered sectors, free allowances will be phased out as from 2026, as the CBAM financial adjustment is phased in according to a gradual schedule.

To complement the ETS, the CBAM will be based on a system of certificates to cover the embedded emissions in products being imported into the EU. The CBAM departs from the ETS in some limited areas where it was needed for a border adjustment instrument, as it is not a ‘cap and trade’ system. Nevertheless, the CBAM certificates mirror the ETS price.

Once the full CBAM regime becomes operational in 2026, the system will adjust to reflect the revised EU ETS, in particular when it comes to the reduction of available free allowances in the sectors covered by the CBAM. This means that the CBAM will only begin to apply to the products covered and in direct proportion to the reduction of free allowances allocated under the ETS for those sectors. Put simply, until they are completely phased out in 2034, the CBAM will apply only to the proportion of emissions that does not benefit from free allowances under the EU ETS, thus ensuring that importers are treated in an even-handed way compared to EU producers.

Which sectors will the new mechanism cover and why were they chosen?

The CBAM will initially apply to imports of the following goods:

• Cement

• Iron and Steel

• Aluminium

• Fertilisers

• Hydrogen

• Electricity

These sectors have been selected following specific criteria, in particular their high risk of carbon leakage and high emission intensity which will eventually – once fully phased in –represent more than 50% of the emissions of the industry sectors covered by the ETS.

The CBAM will apply to direct emissions of greenhouse gases emitted during the production process of the products covered, as well as to indirect emissions for a subset of those products (i.e. cement and fertilisers). The CBAM Regulation provides that an analysis will need to be carried out before including indirect emissions in further products in the future. A review of the CBAM’s overall functioning during its transitional period will also be concluded before the entry into force of the definitive system.

At the same time, the product scope will be reviewed by the end of the transitional period to assess the feasibility of including other goods already covered by the EU ETS and susceptible to carbon leakage, such as certain downstream products and those identified as suitable candidates during negotiations (i.e. chemicals and polymers).

The report will include a timetable setting out their inclusion by 2030.

Will the CBAM apply to EEA countries?

The CBAM has EEA relevance and is designed to take full account of the carbon price paid in third countries, whether through market-based instruments like the ETS, or through carbon taxation. Goods originating in countries that fully apply the EU ETS – such as EEA countries – or that have concluded an agreement fully linking their ETS with the EU ETS – such as Switzerland – are entirely excluded from the mechanism.

By ensuring importers pay the same carbon price as domestic producers under the EU ETS, CBAM will ensure equal treatment for products made in the EU and imports from elsewhere and avoid carbon leakage.

How is the CBAM compatible with other ETS systems outside the EU?

The CBAM will ensure that imported products will get “no less favourable treatment” than EU products, thanks in particular to 3 CBAM design features:

– the CBAM takes into consideration “actual values” of embedded emissions, meaning that decarbonising efforts of companies exporting to the EU will lead to a lower CBAM payment,

– the price of the CBAM certificates to be purchased for the importation of the CBAM goods will be the same as for EU producers under the EU emissions trading system (EU ETS), and

– the effective carbon prices paid outside the EU will be deducted from the adjustment to avoid a double price.

This carbon price paid in a third country could for example be due to an established Emissions Trading System. The Commission will develop secondary legislation before the end of the transitional period to design the rules and processes to take in to account the effective carbon price paid abroad. During the transitional period, the reports will need to include the carbon price due in a country of origin for the embedded emissions in the imported goods, taking into account any rebate or other form of compensation available, for information purposes.

Transitional Period

What will happen in the transitional period?

During the transitional period starting on 1 October 2023 and finishing at the end of 2025, importers will have to report at the end of each quarter emissions embedded in their goods subject to CBAM without paying a financial adjustment, giving time for the final system to be put in place.

This transitional period, combined with the gradual phasing-in of CBAM between 2026 and 2034, will allow for a careful, predictable and proportionate transition for EU and non-EU businesses as well as authorities.

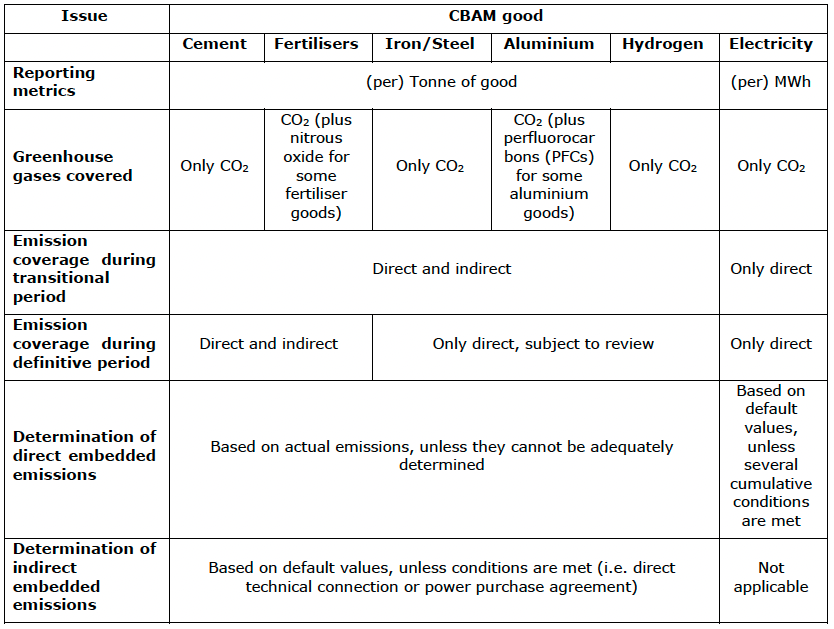

What specific information needs to be reported by each CBAM covered sector?

The following table provides an overview of the specific emissions and greenhouse gases covered and how direct and indirect emissions will be determined for each sector under the CBAM scope. Each sector’s particularities have been taken into account when designing the methods for reporting and calculating embedded emissions in these goods while mirroring the EU Emissions Trading System:

CBAM reporting obligation

Who is responsible for the reporting?

Customs authorities will inform customs declarants of their obligation to report information during the transitional period. The customs declarant will either be the importer or the indirect customs representative depending on who lodges the customs declaration.

The person responsible for the reporting obligation can be one of the following:

1. the importer when (i) the importer lodges a customs declaration for release for free circulation of goods in its own name and on its own behalf; and when (ii) is also the declarant holding an 5ertificate5n to lodge a customs and declares the importation of goods;

2. the indirect customs representative, where the customs declaration is lodged by the indirect customs representative appointed in accordance with Article 18 of Regulation (EU) No 952/2013, when the importer is established outside of the Union; or when an indirect customs representative has agreed to the reporting obligations in accordance with Article 32 of Regulation 2023/956.

What are the reporting obligations?

During the transitional period of the CBAM, from 1 October 2023 until 31 December 2025, the importer shall submit a CBAM report on a quarterly basis. This report will include the information on the goods imported during that quarter of year and should not be submitted later than one month after the end of that quarter.

More concretely, the report shall include the information referred in Article 35 of the Regulation:

• the total quantity of each type of goods;

• the actual total embedded emissions;

• the total indirect emissions;

• the carbon price due in a country of origin for the embedded emissions in the imported goods, taking into account any rebate or other form of compensation available.

How is a CBAM report submitted during the transitional period?

A CBAM report is submitted using the CBAM Transitional Registry which will be deployed for the use of Economic Operators in the EU as from the 1st of October 2023 together with a set of webinars and trainings which will facilitate the use of the registry and the submission of data during the transitional period.

Do importers of CBAM goods need to be authorised to import CBAM products during the transitional period?

Importers of CBAM goods will not need to be authorised during the transitional period in order to import these goods into the EU. Customs will inform importers of CBAM goods of their reporting obligations at the moment of import.

Are there verification obligations during the transitional period?

No, verification by an external independent body will only be mandatory from 2026.

Role of the European Commission

What is the role of the European Commission during the transitional period?

The Commission will have the following tasks during the transitional period:

• Manage the CBAM Transitional Registry.

• Analyse the impact of CBAM on: Exports, downstream products, trade flows and LDCs.

• Prepare secondary legislation in the form of implementing acts:

o In Q3 2023 on the transitional period (art.35), reporting obligations and reporting infrastructure.

o In Q3 2024 on authorisation of declarants (art.5 and 17), the CBAM registry (art.14) and accreditation of verifiers (art.18).

o In Q2 2025 implementing acts on indirect emissions (annex IV), verification (art.8), carbon price paid (art.9), information for customs (art.25), continental shell (art.2), average ETS price (art.21), CBAM declaration (art.6), methodology (art.7) and free allocations (art.31).

• Prepare secondary legislation in the form of delegated acts during Q3 2024 for the accreditation of verifiers (art.18) and selling and repurchasing of certificates (art.20). If necessary, the Commission will also prepare delegated acts on exempted countries, rules on electricity and anti-circumvention.

• Prepare the methods for calculating and reporting embedded emissions during the definitive period.

• Set up the Common Central Platform where the sale, repurchase of certificates will take place in the definitive period.

Competent Authorities

What is a competent authority?

Each Member State has designated a competent authority, which will carry out the functions and duties as defined in Regulation (EU) 2023/956. The list of authorities will soon be published by the Commission.

What is the role of the competent authorities during the transitional period?

The tasks attributed to the competent authority will increase over time, where initially, during the transitional period, they will have to provide guidance to the importers and customs representatives, they will assist the Commission in the control of the CBAM reports during the transitional period.

CBAM Transitional Registry

What is the CBAM Transitional Registry?

In order to ensure an efficient implementation of reporting obligations, the Commission has developed an electronic database, which will collect the information reported during the transitional period. The CBAM Transitional Registry is a standardised and secured electronic database containing common data elements for reporting in the transitional period, and to provide for access, case handling and confidentiality. The CBAM Transitional Registry is the basis for the development and establishment of the CBAM Registry pursuant to Article 14 of Regulation (EU) 2023/956.

What will the CBAM Transitional Registry be used for?

The CBAM Transitional Registry shall enable communication between the Commission, the competent authorities, customs authorities of the Member States and reporting declarants.

The CBAM Transitional Registry will not be used for enforcement, as the information collected will solely serve to feed onto the data analysis and collection during the transitional period.

Customs

What obligations will customs representatives have?

During the transitional period, as indicated in article 32 Regulation (EU) 2023/956, the reporting obligation applies:

• if the importer is not established in a Member State: the indirect customs representative;

• if the importer is established in a Member State: the importer, or, subject to agreement, the indirect customs representative.

Definitive period

How will the CBAM work in practice during the definitive period?

The CBAM will mirror the ETS in the sense that the system is based on the purchase of certificates by importers. The price of the certificates will be calculated depending on the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances expressed in € / tonne of CO2 equivalents emitted. Importers of the goods will have to, either individually or through a representative, register to take part in the CBAM and buy CBAM certificates.

The certificatees surrendered by the CBAM declarant shall correspond to the amount of embedded emissions of the relevant goods expressed in tonnes of CO2. In any case, the authorised CBAM declarant shall ensure that the number of CBAM certificates on its account in the CBAM registry at the end of each quarter corresponds to at least 80 % of the embedded emissions. In addition, there is a possibility to purchase certificates along the year.

CBAM certificates will be sold by Member States through a common central platform to authorised CBAM declarants established in that Member State. Only authorised CBAM declarants are allowed to purchase certificates. These certificates shall be surrendered via the CBAM registry by 31 May each year being 2027 the first time, for the year 2026.

What will be the role of the European Commission during the definitive period?

The CBAM Regulation stipulates that the new mechanism should be run by the European Commission in coordination with relevant Member States’ competent authorities. Therefore, the Commission will be in charge of reviewing and verifying declarations as well as managing a central platform for the selling of CBAM certificates to importers. From 2026, importers of CBAM goods into the EU will have to declare by 31 May each year the quantity of goods and the embedded emissions in those goods imported into the EU in the preceding year. At the same time, they must surrender the CBAM certificates they have purchased in advance from the Commission.

How is a CBAM declarant authorised and what is the timeline for its authorisation during the definitive period?

The competent authority in the Member State in which the applicant is established shall grant the status of authorised CBAM declarant, when the applicant meets the following criteria:

– has not been involved in a serious infringement or in repeated infringements of customs legislation, taxation rules, market abuse rules or the CBAM Regulation;

– demonstrates its financial and operational capacity;

– is established in the Member State where the application has been submitted;

– has been assigned an EORI number.

A consultation procedure is required before granting the authorisation, and it should not exceed 15 working days.

How can EU importers ensure that they get the information they need from their non-EU exporters to be able to use the new system correctly?

Non-EU producers should provide the information on embedded emissions for goods subject to CBAM to the EU-registered importers of their goods. In cases where this information is not available at the time when the goods are being imported, EU importers will be able to use default values (even once the definitive system has kicked in) on CO2 emissions for each product to determine the number of certificates they need to purchase.

In addition, production sites outside the EU will have the possibility to register in the EU central database to communicate their emissions reports. This should facilitate compliance for any importer of CBAM goods produced in these sites.

Imports of goods from which countries will fall under the scope of the CBAM?

In principle, imports of goods from all non-EU countries will be covered by the CBAM. That said, certain third countries who participate in the ETS or have an emission trading system linked to the Union’s will be excluded from the mechanism. This is the case for members of the European Economic Area and Switzerland.

CBAM will be applied to electricity generated in and imported from third countries including those that wish to integrate their electricity markets with the EU. If those electricity markets are fully integrated and provided that certain strict obligations and commitments are implemented, these countries could be exempted from the mechanism. If that is the case, the EU will review any exemptions in 2030, at which point those partners should have put in place the decarbonisation measures they have committed to, and an emissions trading system equivalent to the EU’s.

How is the reliability of the reported information ensured (e.g. on embedded CO2 emissions)?

The Commission, in collaboration with Member States authorities, will continuously monitor reported emissions and corresponding trade, to identify practices of circumvention and non-compliance with the CBAM Regulation and its implementing acts. In addition, verifications will be carried out during the definitive period, and the report derived from them shall include information on the quantification of direct emissions and how these emissions are attributed to the different types of goods.

Declared embedded emissions should be verified by a verifier, accredited in accordance with Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/2067, who will prepare a verification report. In line with this, CBAM declarations will be accompanied by copies of emissions verification reports.

Penalties shall be imposed when a CBAM declarant introduces goods into the customs territory of the Union without complying with the obligations established in the Regulation.

Is there any criteria to measure if the carbon price system applied in a third country is genuine, in order to be considered in a CBAM application?

Verifications will be carried out in order to ensure that CBAM declarants fulfil the obligations set up in the Regulation (EU) 2023/956 and its implementing act during the transitional period. From the definitive period onwards, as laid out in Article 9 of the CBAM Regulation, the information on a paid carbon price shall be certified by a person independent from the CBAM declarant and the authorities of the country of origin.

What is a carbon price?

As indicated in Regulation (EU) 2023/956, a carbon price is the monetary amount paid in a third country, under a carbon emissions reduction scheme, which can adopt various forms i.e. tax, levy, fee or in the form of emission allowances under a greenhouse gas emissions trading system, calculated on greenhouse gases covered by such a measure, and released during the production of goods.

Under the EU ETS, the cap determines the supply of emission allowances and provides certainty about maximum emissions of greenhouse gases. The carbon price is determined by the balance of that supply against the market demand. In contrast, CBAM Regulation (EU) 2023/956 does not impose a cap on the number of CBAM certificates available to importers.

How do importers report a carbon price or rebate?

CBAM declarants may claim a reduction in the number of certificates to be surrendered when a carbon price has been effectively paid in the country of origin. To proceed with any rebate or other form of compensation, the carbon price has to have been effectively paid, and records of documentation shall be required to demonstrate such payment. The Commission shall lay out the rules for the deduction of a carbon price paid abroad in a future implementing act in accordance with Article 9 of the Regulation.

CBAM Registry

How will I get access to the CBAM Registry in the definitive period?

Once an importer’s application has been authorised by the competent authority, it will be considered an authorised CBAM declarant. Each CBAM declarant will be assigned a CBAM account number by the Commission, which allows access to the CBAM registry.

How can the CBAM report be submitted?

The CBAM report shall be submitted through the CBAM registry by the authorised CBAM declarant.

When a customs declaration has been lodged, the competent authority of the Member State shall register the person in the CBAM registry. The competent authority shall also review the CBAM declaration, and therefore, check that the information from the applicant is complete and in line with Regulation (EU) 2023/956 to grant the authorisation.

Competent authorities are encouraged to exchange information, between themselves and with the European Commission, essential or relevant to the exercise of their duties. In addition, they shall be assisted by the Commission in carrying out their functions under the Regulation (EU) 2023/956.

Customs representatives

What obligations will customs representatives have?

During the definitive period, the CBAM obligations apply to the authorised CBAM declarant (Article 5):

• if the importer is not established in a Member State: the indirect customs representative;

• if the importer is established in a Member State: the importer, or, subject to agreement, the indirect customs representative.

Only authorised CBAM declarants may import goods into the Union (Article 4). It follows that if the importer is not established in a Member State and the indirect customs representative does not have the status of authorised CBAM declarant, the concerned CBAM goods cannot be imported in the Union.

The application to become an authorised CBAM declarant needs to contain information on the names and contact information of the persons on behalf of whom the applicant is acting, if applicable (Article 5(5)(h). This information will be stored in the CBAM Registry.

Next steps

The CBAM will enter into application in its transitional period on 1 October 2023, with the first reporting period for traders ending 31 January 2024. The set of rules and requirements for the reporting of emissions under CBAM will be further specified in an implementing act to be adopted by the Commission after consulting the CBAM Committee, made up of representatives from EU Member States. The Commission will continue setting up the transitional CBAM registry as well as preparing further secondary legislation and carrying out the planned analysis.

The European Commission is preparing detailed guidance for the application of CBAM during the transitional period and is developing training through webinars and e-learning etc. These will include training courses for reporting declarants, third-country operators and EU national authorities. A dedicated website with all information supporting implementation will soon be launched.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Memo

Brussels, 14 July 2023

Carbon border adjustment debate divides EC, steelmakers

European Union steelmakers may be at loggerheads with the European Commission on how a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism can be introduced in Europe, according to views expressed during a European Steelmakers’ Association March 17 webinar that focused on EU climate policy.

Introduction of a CBAM on top of the EU’s current Emissions Trading System would be an “overcompensation” in terms of ensuring a fair market for clean steel and risks not being compatible with World Trade Organization policies, Mette Koefoed Quinn, the European Commission’s head of unit, ETS Implementation and IT, DG Climate Action, told industry representatives on the Eurofer webinar. The ETS currently offers some free allocations to steelmakers to avoid carbon leakage.

Eurofer’s members are meanwhile pressing for the ETS to continue for a transition period of eight years after the CBAM is introduced, during which time free ETS allocations would continue to be made to EU steelmakers, the association’s director general Alex Eggert said.

This transition period should run until a sustainable market for “green” steel is fully formed in 2030, according to the association.

“We’ve had intense discussions with trade lawyers who all confirm that carbon border measures are absolutely compatible with WTO….. and even a combination of the two (CBAM and the ETS) to cover the delta between free allocations and carbon costs at the border is compatible,” Eggert said. Europe’s steel industry has already suffered a competitive disadvantage – estimated to have cost the sector some Eur3 billion in 2018 at current prices – due to the ETS system, where the shortage of free ETS allocation to the sector is currently put at around 20%, he said.

The EU is extremely exposed to international competition, with a high cost susceptibility because the EU imports around 30 million mt of steel a year and exports some 20 million mt/year, according to Eurofer data.

CBAM may be implemented in 2023

The European Parliament March 10 approved the principle of setting up a CBAM and the EC is expected to move ahead with a legislative proposal for its introduction in June, for possible implementation in 2023. Andrei Marcu, founder and executive director, European Roundtable and Climate Change and Sustainable Transition, said that so far the only place that a CBAM has been applied is in California. However, US President Biden is understood to be considering one at national level.

WTO Deputy Director-General Alan Wolff said last month that cooperation between nations will be essential to avoid disputes around carbon border taxes. On March 5 the WTO launched a Trade and Environmental Sustainability joint initiative group with 53 member countries, which is expected to be a forum for the discussion of carbon border taxes.

Under the European Green Deal, the EU steel industry needs to reduce its carbon emissions by 55% from 1990 levels by 2030, and achieve net-zero carbon production by 2050. According to Eurofer’s climate and energy director, Adolfo Aiello, this may involve investments of Eur144 billion including in breakthrough technologies which could increase steel production costs and prices by between 35% and 100% above current levels, as a well as supplies of up to 400 TWh of climate-neutral electricity, seven times more than what the sector purchases from the grid today .

The investments required are expected to come from steel sector companies themselves, public sector bodies such as the EU Innovation Fund, and ETS revenues, around 80% of which are currently being used for “green” actions, according to the EC.

“We support climate ambition but it needs to be achieved in the most cost-efficient way: higher climate ambition means and needs better carbon leakage protection, and more support for low carbon technologies,” Aiello said. Carbon is currently priced in the EU at around Eur40/mt, having risen dramatically over the past three years after hovering around Eur7/mt for several years. This decade carbon prices might even rise to “three-digit” levels, he said.

“Fair burden-sharing is needed between ETS and non-ETS sectors,” he said, adding the commission needs to redirect more of the ETS revenues to industry.

EC considering six options

The EC is looking at six different options to decarbonize, but does not consider that a CBAM could be complementary to the ETS system, Quinn said. It would be an alternative, she said.

Phase 3 of the EC’s ETS allocation system has just finished, without carbon leakage having been seen, she said. In Phase 4 of the ETS, designed to cover the January 2021 to 2030 period, free allocations to companies are now being calculated.

The overall structure of the ETS is being reviewed: there will be sufficient free allocation, to the benefit of steelmakers, Quinn said. “The current system foresees the sufficient allocation of free allowances until 2029-30: giving adequate carbon leakage protection. However, we’re now looking at whether to introduce CBAM… the commission says it’s either CBAM or free allocation, you can’t have both because that’s a risk of double compensation…. but a transition period might be needed and that’s one of the alternatives we’re looking at,” she told the webinar.

While ETS free allocations are currently giving adequate carbon leakage protection, they are reducing the incentive to go for quick decarbonization: “The pricing is not coming through as it should into the products and this is a problem,” Quinn said. CBAM could provide a useful incentive to the steel industry to decarbonize within Europe and externally, she said.

— Diana Kinch

MEPs: Put a carbon price on certain EU imports to raise global climate ambition

To raise global climate ambition and prevent ‘carbon leakage’, the EU must place a carbon price on certain imports from less climate-ambitious countries, say MEPs.

On Wednesday, Parliament adopted a resolution on a WTO-compatible EU carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) with 444 votes for, 70 against and 181 abstentions.

The resolution underlines that the EU’s increased ambition on climate change must not lead to ‘carbon leakage’ as global climate efforts will not benefit if EU production is just moved to non-EU countries that have less ambitious emissions rules.

MEPs therefore support to put a carbon price on certain goods imported from outside the EU, if these countries are not ambitious enough about climate change. This would create a global level playing field as well as an incentive for both EU and non-EU industries to decarbonise in line with the Paris Agreement objectives.

MEPs stress that it should be WTO-compatible and not be misused as a tool to enhance protectionism. It must therefore be designed specifically to meet climate objectives. Revenues generated should be used as part of a basket of own revenues to boost support for the objectives of the Green Deal under the EU budget, they add.

Mechanism to be linked to a reformed EU Emissions Trading System (ETS)

The new mechanism should be part of a broader EU industrial strategy and cover all imports of products and commodities covered by the EU ETS. MEPs add that already by 2023, and following an impact assessment, it should cover the power sector and energy-intensive industrial sectors like cement, steel, aluminium, oil refinery, paper, glass, chemicals and fertilisers, which continue to receive substantial free allocations, and still represent 94 % of EU industrial emissions.

They add that linking carbon pricing under the CBAM to the price of EU allowances under the EU ETS will help to combat carbon leakage but underline that the new mechanism must not lead to double protection for EU installations.

You can watch a video of the plenary debate here.

Quote

After the vote, Parliament rapporteur Yannick Jadot (Greens/EFA, FR) said:

“The CBAM is a great opportunity to reconcile climate, industry, employment, resilience, sovereignty and relocation issues. We must stop being naïve and impose the same carbon price on products, whether they are produced in or outside the EU, to ensure the most polluting sectors also take part in fighting climate change and innovate towards zero carbon. This is our best chance of remaining below the 1.5°C warming limit, whilst also pushing our trading partners to be equally ambitious in order to enter the EU market.

Next steps

The Commission is expected to present a legislative proposal on a CBAM in the second quarter of 2021 as part of the European Green Deal as well as a proposal on how to include the revenue generated to finance part of the EU budget.

Background

Parliament has played an important role in pushing for more ambitious EU climate legislation. It declared a climate emergency on 28 November 2019 and wants the EU and its member states to become climate neutral in 2050 and reduce GHG emissions with 60% by 2030.

Source: europarl.europa.eu